Opinion: Gerrymandering Must Come to an End in this Parliamentary Election!

Recent murmurs in the Maldivian political landscape suggest that the term ‘gerrymandering’, often associated with the intricacies of American politics, is finding resonance closer to home. Traditionally, we’ve only heard of gerrymandering within the context of U.S. Senate elections, with battles fought in the U.S. Supreme Court. But the question now is, why has it garnered attention in our local media?

Unpacking Gerrymandering

For those unfamiliar, gerrymandering is the crafty reconfiguration of electoral boundaries to serve the interests of a specific party or group. Picture a complex network of pipes where the flow of water (symbolizing votes) is directed differently based on design adjustments. Political entities have the potential to channel votes similarly. This art is mastered in two primary techniques:

1. Cracking: Dispersing a voting group across several constituencies to dilute its influence.

2. Packing: Consolidating a voting group in a single constituency to curtail their influence in adjacent ones.

The term originates from a peculiar incident in 1812, where a newly crafted electoral district in Massachusetts, signed into being by Governor Elbridge Gerry, bore a striking resemblance to a salamander. Hence, “Gerry” + “salamander” = gerrymandering.

Could the Maldives fall prey to Gerrymandering?

The foundation of a democratic system is the right to representation. As described above, this right to representation can be diminished through administrative procedures of constituency delineation. Is Maldives’ system susceptible to attempts at undermining the right to representation? Let’s explore a hypothetical situation with respect to parliamentary and local council elections.

The Scenario:

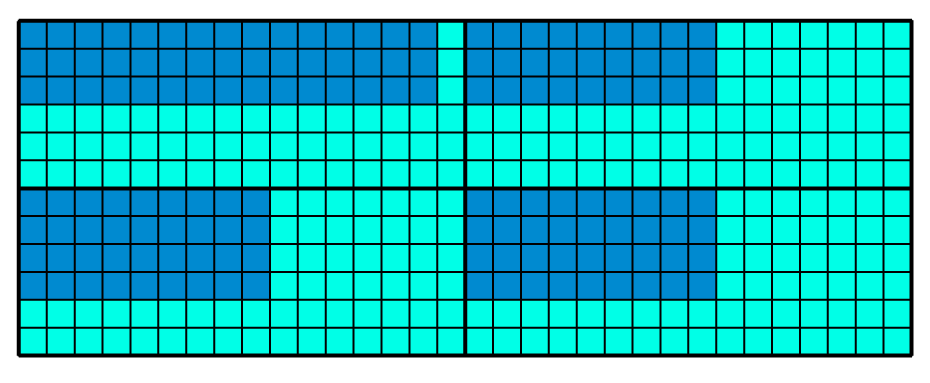

Imagine Island X, shaped like a rectangle for simplicity. This island is divided into four rectangular wards, each with an equal number of residents. All four wards predominantly support Party A, depicted in turquoise. Let’s say there’s a minor presence of Party B supporters, represented in blue, scattered across the island.

Traditional Division:

- In a standard electoral process, each ward becomes a separate constituency. Given the majority support for Party A, all four seats would naturally go to them.

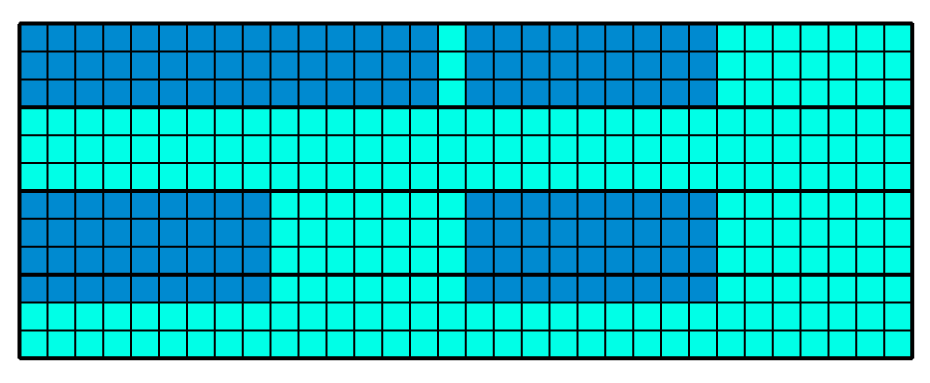

Gerrymandered Division by Party B:

Now, suppose Party B, despite being in the minority and not having control, gains the power to redefine constituencies. Instead of preserving the original wards, Party B redivides Island X into four elongated constituencies, each running from one end of the island to the other. These new constituencies deliberately include a mix of blue and turqouise supporters.

The result? Despite Party A’s majority support on the island, the new boundaries ensure a split outcome: two seats for Party A and two for Party B. This is achieved by ensuring that in two of the newly fashioned constituencies, Party A’s majority is diluted by Party B’s minor presence.

This illustration reveals how electoral boundaries can be tweaked to give one party an undue advantage, skewing representation away from the true will of the electorate.

In the complex tapestry of global democracies, the Maldives boasts a peculiar and unparalleled facet: Male’s Dhaftharu. This free register of residents stands as a stark deviation from the norm. Unlike most democratic systems where voters are assigned to constituencies based on their domicile or established residence, the Dhaftharu offers a dynamic and open-ended means of voter allocation. Exhaustive searches into other democracies yielded no parallels to such a system, making its existence in Male’ a true anomaly. The thought becomes even more unsettling when one contemplates how this openly accessible list — potentially revealing voters’ party affiliations — could be strategically wielded to sculpt the narrative and direction of an election.

Lessons from Abroad

In the U.S., redistricting, similar to adjusting a complex circuit board, occurs every ten years, post the decennial census. While the process aims for fairness, when influenced by a dominant party, it can lead to systemic biases. Notable U.S. Supreme Court cases, like Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004) and Gill v. Whitford (2018), spotlight the challenges posed by gerrymandering.

Not all gerrymandering cases are created equal. Some aim to favour a political party, while others, like Miller v. Johnson (1995), showcase racial gerrymandering, where district lines are redrawn to either amplify or suppress racial minority votes.

In Miller v. Johnson, the Supreme Court ruled against a bizarrely shaped district in Georgia, suggesting it was an attempt to segregate voters based on race. Such cases challenge the very ethos of the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution, which mandates that individuals in similar situations be treated equally by the law.

Defending the Maldivian Ethos

Our constitution, enshrined in Article 17, champions the principles of equality and protection against discrimination. When gerrymandering creeps into the system, it starkly contrasts with the essence of our constitutional values.

To me, the political system unfolds as a marvel of complexity and intricacy. Yet, like any mechanism, it demands regular upkeep and adaptability to the ever-evolving societal, economic, and cultural contexts, ensuring that every citizen’s voice remains on an equal footing.

Disturbingly, our very system provides leeway for gerrymandering, thereby undermining citizens’ rightful representation. Take, for instance, the ad hoc allocation of Dhafthar citizens to constituencies. The inconsistency in reasons from one election to the next raises eyebrows. Gerrymandering emerges as more than a mere oversight; it becomes an intrinsic flaw. While my expertise may not be rooted in law, the idea that nearly 20,000 Dhaftharu individuals could find their voices muted due to electoral machinations is antithetical to the democratic ethos we hold dear.

In Conclusion

Gerrymandering, a concept born on distant shores, now looms ominously over our democratic sanctity. As the Parliamentary Election beckons, the need for vigilance is paramount. It’s our collective responsibility to safeguard the integrity of our political landscape, mindful of the dire ramifications gerrymandering could impose upon the everyday lives of Maldivians.

Nishwan Abbas is an IT and project management expert with foundational studies in civil engineering from University College London and professional qualification in marketing from the Chartered Institute of Marketing. Currently serving as the President of the Guesthouse Association of Fuvahmulah and the owner of Vagary, he specializes in cloud-based solutions and business consultancy. Nishwan often indulges in personal coding projects during his free time. A passionate advocate for civil rights, he upholds a commitment to promoting fairness and equity in society.